Note: This post in no way condones of violence, though the Gospel is necessarily violent. This post contains spoilers but given that the film was released more than three decades ago, this is not really a warning.

Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988) is the perfect Christmas film. I am not the first to make this claim (or something similar). That Die Hard is a Christmas film at all is presented by some as a tongue-in-cheek suggestion, while others argue that Die Hard is simply an action film that takes place during Christmas. The genre of ‘Christmas movie’ is full of tat that presents itself as the ‘true meaning’ or ‘spirit’ of Christmas. Rubbish. For all intents and purposes, the ideas of shared humanity, love, forgiveness, acceptance, and family are lovely and can indeed be perceived as parts of the ‘spirit of Christmas’, though none of these ideals capture the essence of Christmas in the way that only Die Hard does.

How can I claim that Die Hard is the perfect Christmas film? Please indulge me for a moment.

Bruce Willis plays John McClane, a working-class New York City police officer. His estranged wife, Holly Gennero (played by Bonnie Bedelia) has accepted her dream job working for the Nakatomi Corporation. Unfortunately for McClane, Gennero’s new position necessitates that she relocate to Los Angeles, which she does with the couple’s two children, Lucy (Taylor Fry) and John Jr (Noah Land).

As Christmas nears, Gennero waits expectantly for McClane’s arrival: this is the season of Advent, in which the Christian Church rehearses the narrative for the arrival of Jesus of Nazareth, the Messiah. Does this seem far-fetched? Hardly. Apart from what might take place off-screen, we know that Gennero and the children are eager for McClane’s arrival, with Gennero phoning the childminder, Paulina (Betty Carvalho) to ensure that a bed is prepared in her home for McClane (as Gennero would not want the coming Son of Man to sleep in a stable, obviously).

Admittedly, at the beginning of the film, McClane’s role as the Christ is obscured. He comes from the east (NYC→LA) bearing gifts, as we see him carrying a giant teddy bear and it is reasonable to assume that he has other gifts for his children in his luggage (Matthew 2.1-2, 10-11). Therefore, at this stage, McClane represents the ‘wise men’ and he has ventured west under the light of a brilliant star (the Los Angeles sunset features prominently during the whole opening act).

McClane is collected at the airport in a limousine driven by Argyle, one who makes straight the way of the Lord (Matthew 3.3; Mark 1.2; cf. Isaiah 40.3). Soon thereafter, he arrives at Nakatomi Plaza, an under-construction skyscraper in the Century City district of Los Angeles. Here we can see the role of ‘wise men from the East’ shift to another character. The limousine is provided by Gennero’s boss, Joseph Yoshinobu Takagi (James Shigeta), who was born in Kyoto, Japan (most assuredly the ‘East’) and emigrated with his family to the United States in infancy. At Nakatomi Plaza, McClane prepares reluctantly to join a corporate Christmas party. It is at this point that a group of men, led by West German terrorist Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) infiltrates and locks down the building. McClane, who is getting ready for the party in an office, hears gunfire and the panic of party guests. At this stage, he, in his vest and bare feet, withdraws to assess the situation (Matthew 2.13-15).

McClane does his best to alert other authorities to the plight of those in Nakatomi Plaza, first by triggering a fire alarm (which is detected and deactivated by the terrorists) and then by reaching out to the police, using an emergency frequency on a radio he commandeered from a fallen terrorist. McClane’s plea is not taken seriously by the authorities, but a police officer, Sgt Al Powell (Reginald VelJohnson) is called to investigate. Powell does not perceive anything suspicious and is about to depart when McClane gets his attention by throwing the lifeless corpse of one of the fallen terrorists onto the bonnet of Powell’s squad car. Knowing that they have been discovered, the terrorists shower Powell’s car with bullets as he retreats, calling for backup.

Eventually, McClane gets in touch with Powell on his radio. Powell hears McClane’s message and sets himself under McClane’s tutelage. Powell represents all that have ‘ears to hear’ (Mark 4.23; Luke 8.8). Later, Powell also reports that McClane has garnered many more disciples among the police (this being a direct result of Powell’s sharing of the Gospel of John McClane, i.e., evangelism; see 2 Corinthians 5.20).

In contrast to the reception he receives from Powell and his other disciples, the authorities oppose McClane, who see his message as a threat to their own perceived authority. The first authority to oppose McClane is LAPD Deputy Chief, Dwayne T. Robinson (Paul Gleason). When first speaking with Powell, Robinson seeks to erode Powell’s confidence in McClane, suggesting that McClane may be one of the terrorists. In a similar way, the religious authorities in first-century Palestine sought to undermine Jesus’ authority by suggesting to the people that Jesus was an enemy of their religion (for example, see Matthew 12.22-24). Powell insists that McClane’s words are those of an ally (see Matthew 12.33-37). In response, Robinson exclaims, ‘Jesus Christ, Powell!’ Jesus Christ, indeed.

When Robinson is able to speak with McClane directly, he declares, ‘We do not want your help.’ In response, McClane tells Robinson that ‘if [he is] not part of the solution, [he is] part of the problem’, a phrase that may be the converse of Jesus’ words ‘whoever is not against you is for you’ (Mark 9.40; Luke 9.50).

Throughout the opposition McClane faces from authorities, Powell shows consistent commitment to his Teacher. At one point, Powell professes his love for McClane, calling back to Peter telling Jesus that he loves him (John 21.15-17). Due to his great faith in and commitment to McClane, Powell is told by his superior:

Robinson ‘You listen to me, sergeant: any time you wanna go home, you consider yourself dismissed.’

Powell ‘No sir: you couldn’t drag me away.’

Powell is a constant advocate for McClane among the authorities. When Agents Johnson and Johnson (Robert Davi and Grand L. Bush) of the FBI arrive to ‘take over’, Powell insists that McClane has been their guiding light throughout the whole hostage fiasco.

The opposition that McClane faces is not bound to the civic authorities, but also to anyone who seeks power. Enter Hans Gruber, whose guise as ‘terrorist mastermind’ is a cover for the attempted theft of $600m in bearer bonds from the Nakatomi Corporation. Gruber represents Death, the Enemy, or—if you are of that theological persuasion—the Devil. Throughout the film, we witness the death of several people, including two Nakatomi security guards and whoever was in the exploded LAPD SWAT van. These deaths were executed under the direct orders of Gruber. The two personal murders witnessed in the film—the first being that of Takagi and later, coke-snorting, sleazy Judas, Harry Ellis (Hart Bochner)—are at the hands (or pistol) of Hans Gruber. McClane is pursued doggedly by Gruber and his thugs (akin to the actions of King Herod when visited by the wise men). When realising that he and his second-in-command, Karl (Alexander Godunov) have got the bare-foot McClane cornered in an office, Gruber orders Karl to shoot out the glass windows so that McClane will have to cross the broken glass to escape.

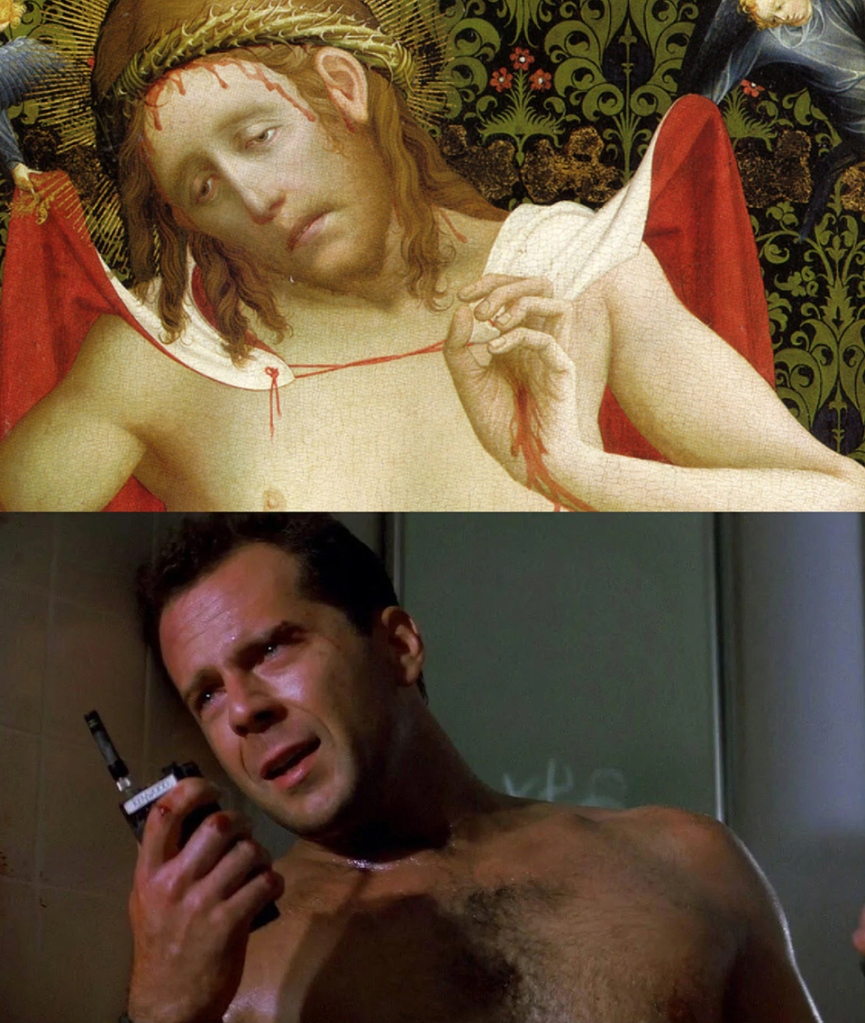

While McClane had been battered relentlessly throughout the ordeal, this part of the film showcases the ‘Suffering of John’ or ‘John of Sorrows’ motif.

Perhaps a protest will be raised that while Die Hard is a masterful retelling of the life of Christ, it is not about Christmas. I defer to the countless Renaissance depictions of both the Nativity and of the Virgin and Child. Many of these depictions convey the breadth of the Gospel story, such as the appearance of Crucifixes (see Lorenzo Lotto’s 1523 depiction of the Nativity, for instance) or certain foliage representing the passion (Hugo van der Goes’ 1475 altarpiece for Tommaso Portinari features white and purple irises that allude to the Passion and three red carnations that allude to the three nails of the Crucifixion). One would be hard-pressed to deny the suitability of these depictions for reflection at Christmastime. Similarly, as Die Hard presents a broad Gospel narrative, this combined with its unmistakably Christmas context qualifies it as a Christmas film.

As the film enters its closing act, we discover that Gruber intends on killing all the hostages with C4 plastic explosive. He does this under his ruse of being a ‘freedom fighter’ and requests a helicopter to airlift his crew and the hostages to the airport. Once the hostages and the helicopter are destroyed on the roof, he believes that he will be presumed dead, thus making an easier escape with his bounty of bearer bonds in a van with Los Angeles City Fire Department markings. McClane is wise to Gruber’s plan and fights his way to the roof to clear the hostages from the helipad. Here, he puts himself in between the hostages and the FBI authorities (who have arrived in gunships to kill the terrorists instead of flying them to the airport). McClane’s actions saved the lives of all hostages, while the scheming FBI agents (who expressed contentment with the prospect of losing up to 25% of the hostages) met their end in the subsequent explosion.

This putting of himself in between the people and their enemies demonstrates just one of many ways that John McClane is the Christ-figure of Die Hard. In 1 Corinthians 15, St Paul enlightens us to the all-encompassing work of Christ, in particular, the work of Christ that culminates in the Crucifixion and Resurrection:

But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have died. For since death came through a human being, the resurrection of the dead has also come through a human being; for as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ. But each in his own order: Christ the first fruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ. Then comes the end, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father, after he has destroyed every ruler and every authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death. For ‘God has put all things in subjection under his feet.’… When all things are subjected to him, then the Son himself will also be subjected to the one who put all things in subjection under him, so that God may be all in all.

It is through McClane that the remaining attendees of the Christmas party at Nakatomi Plaza were ‘made [or rather, kept] alive’. He destroyed ‘every ruler and every authority and power’ when he disposed of Hans Gruber’s henchmen one-by-one. Then, the ‘last enemy to be destroyed is death.’

Shirtless, shoe-less and wounded severely, John McClane’s steadfast commitment to his calling brought salvation to many. What is Die hard if not the Christmas story?

It is valuable to acknowledge the Virgin Mary in any Christmas narrative. I am not suggesting that Gennero is Mary, but that the empowerment of women is at the very heart of the Gospel. Gennero is not some helpless maiden throughout Die Hard. She attempts to keep Takagi out of harm’s way when Gruber is trying to find him in the crowd of partygoers. She shows courage and solidarity at every step. There is, of course, a share of sexism in Die Hard (though I would argue that John’s disappointment in Holly dropping the ‘McClane’ surname is more to do with his pain at the breakup of their marriage, rather than a patriarchal hold on her life), but Gennero’s independence and empowerment is demonstrated further by one of the last scenes in the film. When she and McClane are approached by the unscrupulous reporter Richard Thornburg (William Atherton), she makes sure to give him a ‘piece of her mind’ for his despicable violation of the family’s privacy.

(It is also worth noting that Peter Venkman [Bill Murray] confirmed that Thornburg—in his previous career as an EPA investigator going by the name Walter Peck—‘has no penis’.)

Happy Christmas and yippee ki yay, motherf*ckers.