THE MIRROR & THE TELESCOPE, PART IV: THE HERMENEUTICAL KEY

The dual subject view of biblical revelation obviously raises questions of how we should understand what the Bible is disclosing to us and how we may use Scripture to theological ends. Witherington proposes that, in reading Scripture, we need to ask the question “in what sense, and in regard to what subject, is this text telling the truth?” He sees value in distinguishing between genres as a starting point for understanding the subject of revelation: “In oracles [prophetic words], we can expect the will and character of God to be most clearly reflected. Prayers and songs that come from the human heart may well tell us the truth about ourselves rather than about God’s character. And narratives can reveal both of these sorts of truths.” (25) While this is moving in the direction of the approach I am advocating, I’m not certain that these broad strokes are completely helpful. First, prayers and songs may indeed reveal God’s nature or plans, not merely human experience. Second, Witherington’s generic distinctions still leave the largest portions of Scripture, which are narratives, in an ambiguous position. Finally, sometimes we find false prophets speaking in oracles, so even the trustworthiness of prophecies require some level of discernment.

Pinnock points to the classical rule of context in hermeneutics: “We must pay attention to who is speaking and what is being said to us in each place [in the Bible].” (84) However, if we put our confidence exclusively in the character of the speakers, we may find that sometimes those who are opposed to God may end up revealing truth (e.g. the pagan prophet Balaam in Numbers 22-24 or the Jewish high priest Caiaphas in John 11:49-52) while those who are God’s prophets may utter something questionable. An example of this is found in Aaron’s commendation for the Hebrews to worship the golden calf he had fashioned as YHWH. We also find in Habakkuk 1:2 and 1:13 an example where the prophet, speaking in an oracle, says that God does not listen to his cries for help and that God’s “eyes are too pure to behold evil, and…cannot look on wrongdoing.” Although we may say this reflects a human emotion or desire to lift up God’s holiness, it is uttered in a form where we would expect it to be theologically accurate—yet we can see that God did hear Habakkuk’s cries and in fact does see evil and wrongdoing. So sometimes where we may expect to find corrupt fallible humanity, we may actually discover divine truth; where we expect to hear God’s perfect voice, we may find the truth of human longing, pain, or other experiences.

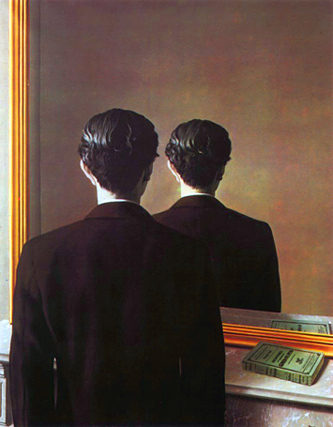

Though this dual-subject theory of revelation adds a great deal of tension to our biblical interpretive strategies, there does exist a key that may help us understand and clarify the revelation of humanity and divinity in Scripture: the God-man, Jesus Christ. As we saw in the original analogy of the mirror and the telescope, we may see Jesus as the mirror in the telescope—perfect humanity who is near to us, revealing the perfect divinity of the transcendent Godhead who is far off. Pinnock uses this analogy himself as he proclaims, “in Jesus Christ, the divine nature is mirrored.” In a lengthier quote, he says

Jesus Christ is and must be the centerpiece of the Christian revelation, because in Jesus God entered our world within the parameters of a human life…The Scriptures exist to bear witness to him (John 5:39), and he is the sum and substance of their message. No mere emissary of the prophetic sort, the Son is God incarnate, dwelling among us, the revelation of God without peer. Of all the forms of revelation, this is the best. (Scripture Principle, 36)

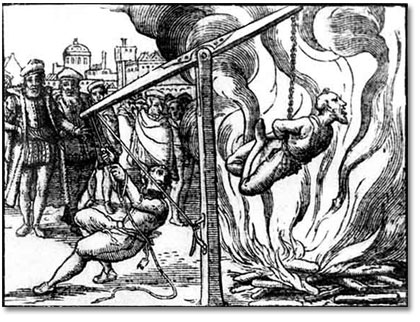

As we consider the human and divine subjects in the totality of Scripture, we can measure them against the One who was perfectly human—understanding our experiences and tendencies while remaining sinless—and who was also perfectly divine—the “reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being” (Heb. 1:3). So, for instance, when we look at Psalm 137 and wonder if smashing babies’ heads against rocks represents God’s desire for humans, we can look at the words and actions of Jesus who commanded us to love our enemies (Matt. 5:44) and who, “when he was reviled, he did not revile in return; when he suffered, he did not threaten” (1 Peter 2:23). As Jesus exemplified true humanity, we can derive our understanding of the anthropological ideal from him and discern whether other Scriptures reveal true examples of fallen human behavior or examples of redeemed human character which we should emulate.

By the illuminating power of the Holy Spirit, we must undertake the project of properly understanding revelation as God both making himself known to us, as well as revealing the truth of our own humanity to us, by using Christ himself as the hermeneutical key to distinguish between what is true of humanity and what is true of God (and conversely, what is false about both). While this is not a simple operation, I believe that this provides the best basis we have for understanding the anthropological and theological dimensions of Scripture. How do we do this exactly? I’m not fully sure. This is indeed the experiment which I am seeking to undertake: re-reading the whole Bible, Old and New Testaments, and discerning between human and divine subjects, with Christ as the hermeneutical touchstone (while also necessarily leaving room for some unanswerable, ambiguous passages along the way).

In his book, Incarnation & Inspiration, Peter Enns describes what he calls a “Christotelic hermeneutic” for reading the Old Testament (which deals with the New Testament use of the OT). I echo the sentiments he shares about pursuing his method as I contemplate the dual-subject approach outlined above; he writes that a coherent reading of the OT using his hermeneutic “is not achieved by following a few simple rules of exegesis. It is to be sought after, over a long period of time, in community with other Christians, with humility and patience.” (170) I would love to read alongside any others who are willing to consider this approach and together rediscover, perhaps more accurately, what the Bible has to say about God and humanity in its pages.

Works Cited:

- Donald Bloesch, Holy Scripture: Revelation, Inspiration & Interpretation, (Downers Grove: Inter Varsity Press, 1994).

- Peter Enns, Inspiration & Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament, (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005).

- Carl F.H. Henry, “Revelation, Special,” Evangelical Dictionary of Theology 2nd ed., ed. Walter A. Elwell, (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2001), 1021.

- I. Howard Marshall, Biblical Inspiration, (1982; repr., Vancouver, BC: Regent College Publishing, 2004).

- Clark H. Pinnock and Barry L. Callen, The Scripture Principle: Reclaiming the Full Authority of the Bible 3rd ed., (1984; Lexington, KY: Emeth Press, 2009).

- Ben Witherington III, The Living Word of God: Rethinking the Theology of the Bible, (Waco, TX: Baylor UP, 2007).