Let me begin by stressing that this post is by no means an exhaustive or thorough look at this particular issue, but rather a starting point for a conversation and potential implications we can draw out for understanding the our existence in the kingdom of God, thus impacting the way we approach life in the kingdom, as is the case with all Imaging the Kingdom.

The concept of the ‘Self’ is one of great importance in the conversation of modern philosophy and Western society at large. This can take the form of investigations regarding the composition of the Self, for instance, a Scientologist might argue that the Self is composed of one’s ‘thetan’ (similar to the concept of one’s ‘spirit’). But what composes the Self in this particular sense (essence) is not the concern of this post. We will rest upon our holistic assumptions from previous ‘Imaging the Kingdom’ posts: God is the Ruler of the universe that he has created, visible and invisible. An individual will not be broken down into separate parts, as God is concerned for and invested in both in the Christian tradition.

Many modern philosophers have concerned themselves with the concept of the Self as if we can attain it through our own clever thought processes. Just as one cannot repair a hammer with said hammer, so one cannot, as a Self, step outside of said Self. In his Treatise on Human Nature, Hume writes,

For my part, when I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble on some particular perception or other, of hear or cold, light or shade, love or hatred, pain or pleasure, I never catch myself at any time without a perception, and never can observe anything but the perception.

(David Hume, Treatise on Human Nature, Book I, Part IV, Sec. VI)

According to Hume, the concept of the Self can amount to, as Russell put it, ‘nothing but a bundle of perceptions’. This non-religious observation can actually assist us in our kingdom-oriented task as it can be deduced that the confidence with which, say, I perceive my Self as an individual should be softened. But the case is not closed there by any means. Hume’s conclusion does not entirely negate the value of this ‘bundle of perceptions’, but rather redefines it. As long as we are redefining the Self in light of our inability to look inward in any objective sense, I believe that the principles of the kingdom of God have profound implications for our definition.

In exploring the answer to the question ‘What is man?’ in his essay ‘The Christian Proclamation Here and Now’, Barth states,

Man exist in a free confrontation with his fellow man, in the living relationship between a man and his neighbour, between I and Thou, between man and woman. An isolated man is as such no man. ‘I’ without ‘Thou’, man without woman, and woman without man is not human existence. Human being is being with other humans. Apart from this relationship we become inhuman. We are human by being together, by seeing, hearing, speaking with, and by standing by, one another as men, insofar, that is, as we do this gladly and thus do it freely.

(Karl Barth, God Here and Now [London: Routledge, 2003], 7.)

Although Barth is answering the question ‘What is man?’ and not ‘What is the Self?’, we see community as a God-given (and necessary) setting for human existence.

Writing more specifically regarding the Self in the opening pages of The Sickness Unto Death, Kierkegaard describes the ‘Self’ as,

The self is a relation which relates to itself, or that in the relation which is its relating to itself. The self is not the relation but the relation’s relating to itself. A human being is a synthesis of the infinite and the finite, of the temporal and the eternal, of freedom and necessity. In short a synthesis. A synthesis is a relation between two terms. Looked at in this way a human being is not yet a self.

In a relation between two things the relation is the third term in the form of a negative unity, and the two relate to the relation, and in the relation to that relation; this is what it is from the point of view of soul for soul and body to be in relation. If, on the other hand, the relation relates to itself, then this relation is the positive third, and this is the self.

(Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death [London: Penguin Books, 2008], 9-10.)

In this way the self is fully understood in the relationship. This is a relationship with the Self and relationship with the creator of the Self. Relationship is the basis for any human understanding of anything and no less for a proper understanding of the Self.

In light of Barth and Kierkegaard’s insights, a human is only truly human in community with God and man. This conclusion very closely resembles the Greatest Commandments (Matthew 22:36-40). In the kingdom of God an understanding of the Self ought to be similarly characterised by God’s intentions for the Self.

Perhaps the greatest theological tenet in the Christian tradition to attest to the necessary communal aspect of existence can be found in the Trinity. Two contemporary theologians who have some very helpful insights for this discussion are John Zizioulas and Leonardo Boff. Zizioulas represents an important bridge between the Eastern and Western traditions (drawing from the work of Vladimir Lossky). Heavily influenced by the Cappadocian Fathers, Zizioulas derives that communion is an ontological category and that God exists in communion. Therefore, Vali-Matti Kärkkäinen summarises, “there is no true being without communion; nothing exists as an ‘individual’ in itself…Human existence, including the existence of the church communion, thus reflects the communal, relational being of God.” (Vali-Matti Kärkkäinen, The Trinity: Global Perspectives, [Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2007], 90.) In this way, without the doctrine of the Trinity there would be no God.

In Trinity and Society, Boff states, “The Trinity is not something thought out to explain human problems. It is the revelation of God as God is, as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” (Leonardo Boff, Trinity and Society [Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1998], 3.) Boff argues that humanity is given a guide through this specific revelation by which to structure society.

Gathering the tools before us we can develop a picture of what the Self might properly look like in the kingdom of God:

- From Hume we can argue that an individual cannot objective conceive of the Self, but rather ‘a bundle of perceptions’ that fall short of the Self.

- From Barth we can argue that it is God’s intention for the individual to find fullest existence in community.

- From Kierkegaard we can argue that the Self is only properly understood in Hegelian relational terms – the individual, the creator and the witness of that relationship.

- From Zizioulas we can argue that the communal aspect of God is absolutely essential to his being, that the Trinity is not an appendix to Christian theism, but its heart.

- From Boff we can argue that human society ought to be structured based upon the community of the Trinity.

So where does this leave us?

Perhaps the reason for the philosophical dilemma of the Self is the fact that we’ve been taking our cues from the wrong place. If it is God’s nature to necessarily exist in the communion of the Trinity, perhaps it is no surprise that our being is also of a communal nature. In the kingdom of God the individual is not called to be alone but in community. In such a way a fuller understanding of the Self is possible, for instance:

As I relate to myself I experience all that is unique to that experience. As I relate to, say, Greg, he is able to see and experience something unique to his perspective of me.

As we relate, these things are synthesised and a fuller picture of the Self is possible. Through the differences that Greg and I encounter in one another God has designed us to act as signposts for one another to himself and his ‘otherness’.

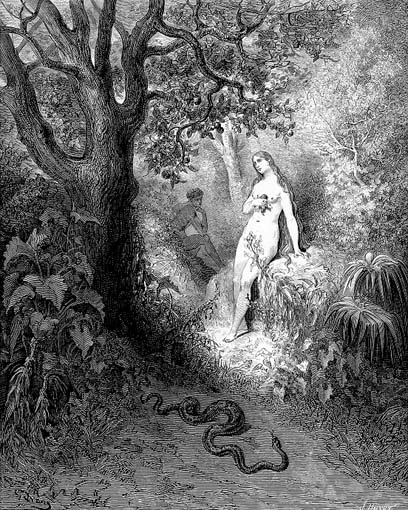

As we look toward God we discover that Christ has come to redeem the entire world and to give humanity a new paradigm to live out of, including a new method of ‘discovering the Self’. A member of the kingdom of God has a new identity, one independent of who we once thought we were and who we may still think we are. As we relate to God we are transformed into his design for the Self. To consider us as individuals the supreme experts regarding our ‘Self’s outside of God’s intentions as demonstrated in the establishing of his kingdom through the Gospel is to ignore the reign and active investment of God in our lives. To embrace the concept of the Self that finds its fullest meaning in relating to God and to others in love we will experience the greatest blessing – the blessing that flows from active participation in and submission to the kingdom of God. In this way we ought to take seriously the call to relate to others, for it is antithetical to ‘the Self in the kingdom of God’ when we do not.

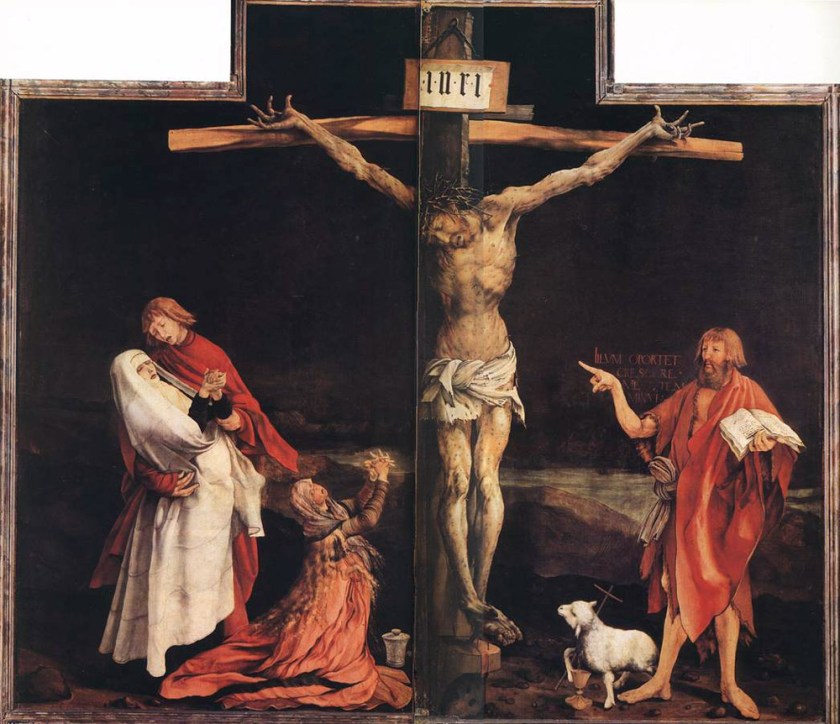

We believe in one God, the Father All Governing, creator of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible;

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten from the Father before all time, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten not created, of the same essence as the Father, through Whom all things came into being, Who for us [humans] and because of our salvation came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary and became human. He was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered and was buried, and rose on the third day, according to the Scriptures, and ascended to heaven, and sits on the right hand of the Father, and will come again with glory to judge the living and dead. His Kingdom shall have no end.

And in the Holy Spirit, the Lord and life-giver, Who proceeds from the Father, Who is worshiped and glorified together with the Father and Son, Who spoke through the prophets; and in one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church. We confess on baptism for the remission of sins. We look forward to the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen.

(Creed taken from John H. Leith (ed.), Creeds of the Churches [Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1982], 33.)