1. Bob Dylan

Surprise, surprise – Bob Dylan is my favourite ‘band’. From a critical perspective, Dylan’s monumental place in the history of popular music is indisputable, yet despite his massive popularity and critical enshrinement, he is and has ever been elusive, in a constant state of artistic evolution. In Martin Scorsese’s 2005 documentary No Direction Home, Dylan states, ‘I had ambitions to set out to find…this home that I’d left a while back. … I was born very far from where I’m supposed to be so I’m on my way home.’

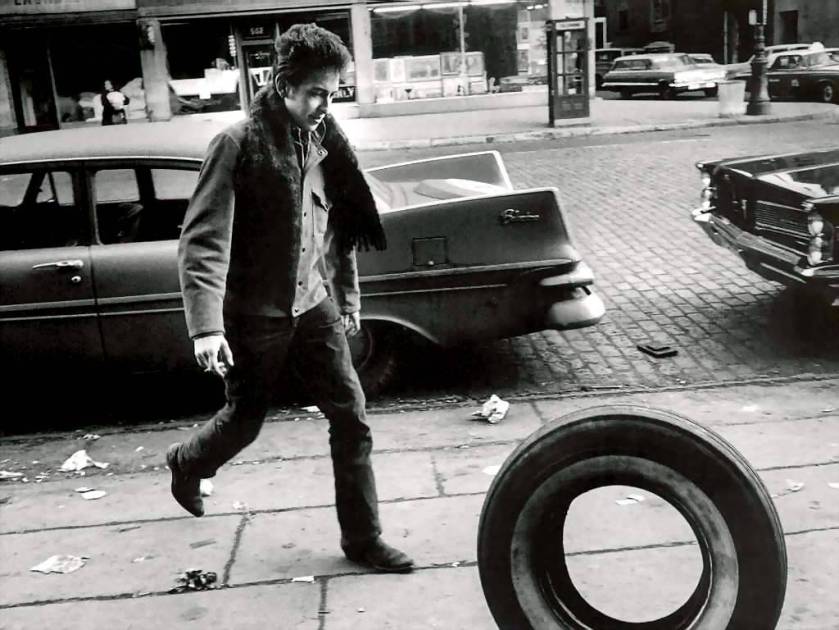

In Greenwich Village, the epicentre of the post-McCarthy folk revival in the early sixties, Dylan would pick out which performers were ‘doing it for real’ and then pick up how they were doing it. Dylan states regarding performers he admired, ‘[There] was something in their eyes that said “I know something you don’t know” and I wanted to be that kind of performer.’ He describes the folk scene in the early 60s as divided into two camps: pop music for college kids and intellectual folk music – Dylan considered himself neither. In his 2006 autobiography Chronicles, Volume One he writes,’ There were a lot better singers and musicians around [Greenwich Village] but there wasn’t anybody close in nature to what I was doing.’ (London: Pocket Books, 18)

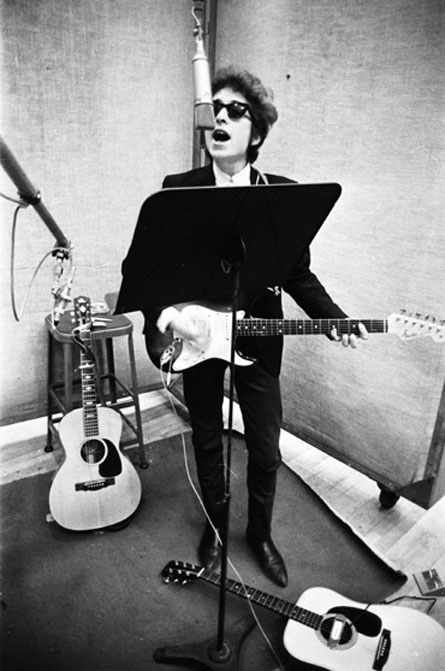

Eventually Dylan’s uniqueness brought him to the attention of Columbia Records’ John Hammond and although Dylan’s voice was not the standard at Columbia—home to the beautiful voices of those like Tony Bennett and Johnny Mathis—Hammond’s track record for sales convinced the executives at Columbia that Dylan would be worth their investment. It was with Columbia that Dylan’s massive repertoire (over 600 original compositions) would take off and progress over the course of the last half-century.

Throughout his career Dylan’s music has undergone several significant shifts. In 1965 he ‘went electric’ with Bringing It All Back Home. This transition brought about accusations of ‘going commercial’ for money and fame. Famously, one audience member criticised Dylan, exclaiming ‘Judas!’ during a now-infamous performance at Royal Albert Hall in 1966.

In a 1965 interview with the Chicago Daily News, Dylan stated, ‘I’ve never followed any trend, I just haven’t the time to follow a trend. It’s useless to even try.’ Instead, Dylan saw his ‘going electric’ as a natural progression from his earlier style. In No Direction Home, he states, ‘An artist has got to be careful never really to arrive at a place where he thinks he’s at somewhere. … You’re constantly in a state of becoming.’

In 1966, not long after the release of his third electric record, Blonde on Blonde, Dylan was injured badly in a motorcycle accident. ‘Truth was that I wanted to get out of the rat race,’ Dylan writes. ‘Having children changed my life and segregated me from just about everybody and everything that was going on.’ (Chronicles, 114) He refrained from touring for the next eight years, but still wrote and recorded prolifically. During this time he returned to more traditional roots and explored country music with several excellent pieces such as ‘I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine’, ‘Lay, Lady, Lay’, ‘If Not For You’ and ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’, but had not achieved a significant amount of critical or commercial success—at least anything that could be likened to the success of his earlier material—until the release of Blood on the Tracks in 1975.

Dylan describes Blood on the Tracks as a product of his ‘painting period’ in which the songs were more ‘like a painter would paint’ rather than those a musician would compose. In The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan, Carrie Brownstein writes, ‘By examining music from a visual perspective, with colours and lines instead of notes and chords, Dylan laid out on the canvas what would be Blood on the Tracks.’ (Kevin J. H. Dettmar, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan, Part I [Cambridge: Cambridge, 2009], 157).

As can be observed from many of his early influences such as Hank Williams’ ‘When God Comes and Gathers His Jewels’ and Woody Guthrie’s ‘Jesus Christ’, Dylan was not unfamiliar with the usage of religious motifs. He employed them in his own work on a regular basis, as is the case with ‘Masters of War’, ‘With God on Our Side’, ‘All Along the Watchtower’, etc. At the time, these expressions were not so much a matter of Dylan’s personal faith as they were the custom of the tradition he was drawing from and his employment of the language of a largely ‘Christian’-literate American society. But by the mid-seventies Dylan began to gain greater interest in religion and God. In a 1975 interview for People magazine Dylan expressed, ‘I’m doing God’s work. That’s all I know.’ Dylan’s interest in faith continued to grow in the late 70s and he converted to Christianity in 1978. Not long after this he began work on his first ‘born-again’ record, Slow Train Coming. Regardless of however outspoken and off-putting Dylan’s conversion might have been to many fans at the time, the single ‘Gotta Serve Somebody’ earned him his first Grammy Award for ‘Best Vocal Performance’ in 1979.

As Dylan had unwittingly become the spokesperson for the folk elitists in the early sixties, he found himself in a similar predicament with regard to the religious community in the eighties. With his 1983 release, Infidels, Dylan began distancing himself from any explicit avowal of faith and the institutions to which he was inevitably linked. After Infidels, Dylan experienced what may be considered a creative, critical and commercial lull. In 1997 he released his ‘comeback’ album Time Out of Mind, which was followed by a string of successes: “Love and Theft” (2001), Modern Times (2006) and Together Through Life (2009). In No Direction Home, artist, musician and friend of Dylan, Bob Neuwirth comments, ‘I think [Dylan] always made exactly the work he wanted to make at the time he wanted to make it. The audience came to Bob.’

While I can’t deny that his work from the mid-eighties through the early-nineties is not my favourite, the magic of Dylan’s music and his ability to constantly reinvent himself en route to ‘becoming’ have significantly shaped the way I see music and how I both personally and creatively interact with the world. Because of this profound and unparalleled impact in my life he belongs nowhere but in this number one slot.

Three of his records can be found on my Top 50 Albums list (and actually reveal my partiality to his earlier material): The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963), The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964) and Blonde on Blonde (1966).

‘Chimes of Freedom’ from Another Side of Bob Dylan, live at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964:

‘Like A Rolling Stone’ from Highway 61 Revisited, live at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965:

+++++

In addition to his massive discography, here are some titles of suggested books and films related to Dylan:

- The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia by Michael Gray (London: Continuum, 2006)

- Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews edited by Jonathan Cott (New York: Wenner Books, 2006)

- The Bob Dylan Scrapbook: 1956-1966 by Bob Dylan (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005)

- The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan edited by Kevin J. H. Dettmar (Cambridge: Cambridge, 2009)

- Chronicles, Volume One by Bob Dylan (London: Pocket Books, 2006)

- Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited by Clinton Heylin (New York: William Morrow, 2001)

- Lyrics, 1962-2001 by Bob Dylan (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006)

- Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Vol. 1: 1957-73 by Clinton Heylin (London: Constable, 2010)

- Still on the Road: The Songs of Bob Dylan, Vol. 2: 1974-2008 by Clinton Heylin (London: Constable, 2010)

- Tarantula, an experimental novel written by Bob Dylan from 1965-6 (New York: Harper Perennial, 2005)

- Dont Look Back, documentary covering Dylan’s 1965 tour of the UK, directed by D.A. Pennebaker (1967)

- Festival!, documentary of the Newport Film Festival from 1963-5, directed by Murray Lenner (1967)

- I’m Not There, semi-biographical film, ‘Inspired by the music and the many lives of Bob Dylan’, directed by Todd Haynes (2007)

- No Direction Home, documentary on Dylan’s early life and his career prior to his touring hiatus in 1966 following his motorcycle accident, directed by Martin Scorsese (2005)

+++++

Top 20 Bands (as of May 2012)

I find that I am usually imitating / shamelessly stealing from Bob Dylan whenever I try to write a song. I mourn the destruction that time, cigarettes and various substances have done to his voice. I recently had the idea to host a Bob Dylan film festival: No Direction Home, Don’t Look Back, The Other Side of the Mirror–maybe throw in Pat Garret and Billy the Kid and I’m Not There for good measure…

Great list, Elijah! Loved reading your insights.

Judy,

Thanks for reading and sharing. I’m glad you enjoyed the list. The Bob Dylan film festival idea has cropped up in my mind on occasion also. Does that mean we’re both cool or that we’re both pathetic?